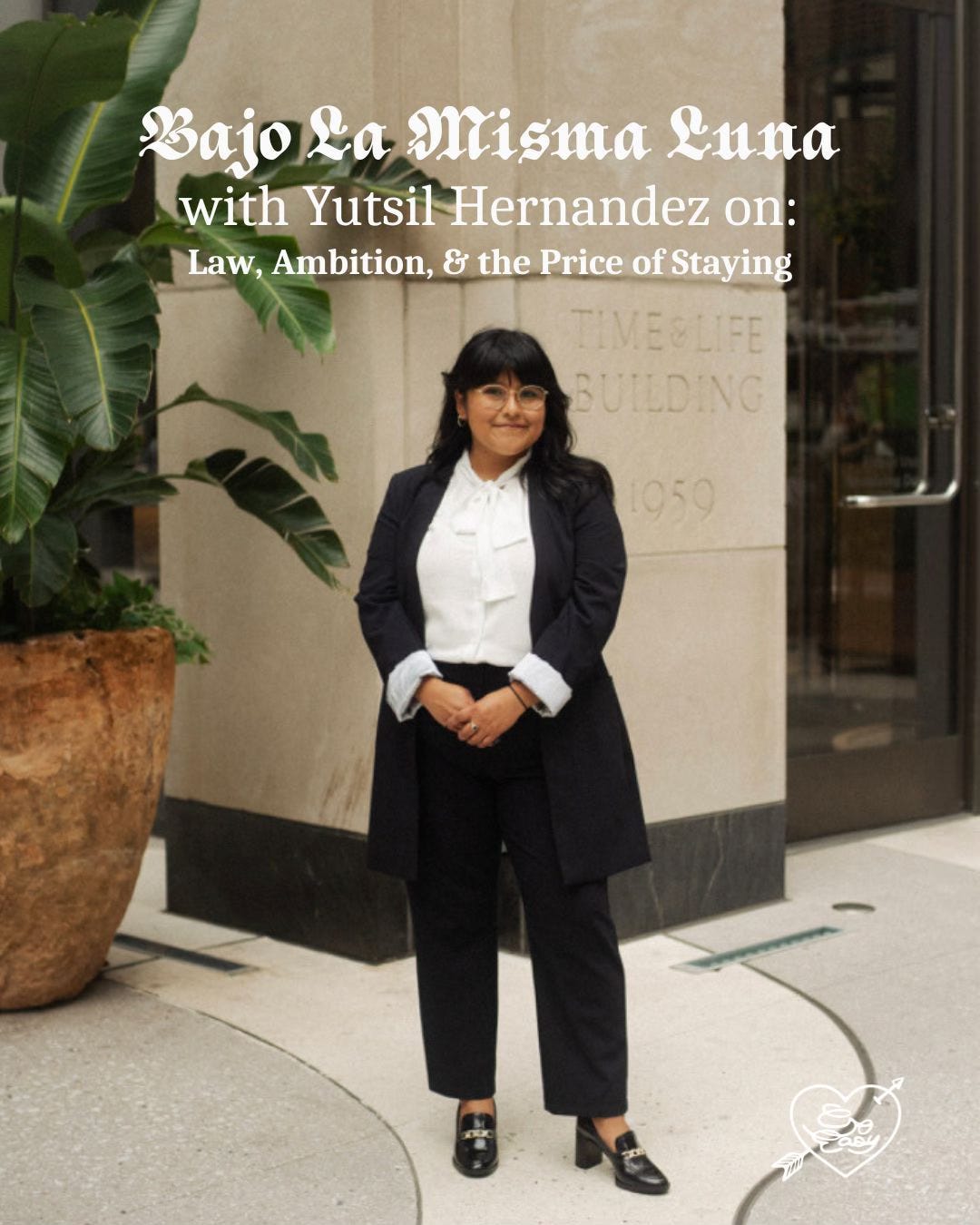

Bajo La Misma Luna w/ Yutsil Hernandez

on Law, Ambition, & the Price of Staying

People tend to start stories where they officially “begin”. I like to start stories where one’s body begins.

Yutsil’s story began in Mexico City.

She moved to the U.S. at six, which is an age where you can still believe the world is made of open doors, until you learn how many are locked.

She grew up in North Carolina. Went to school there. Excelled. Did everything that children are told to do when the promise is that education will lead somewhere.

But when it came time for college, the promise stalled.

Because immigration law does not care how long you’ve lived somewhere. It does not care how well you’ve done. It does not care how young you were when you arrived. Yutsil couldn’t qualify for in-state tuition, even though North Carolina was the only school system she had ever known. Which is a special kind of cruelty: being raised somewhere and still being told you don’t belong to it.

So she did what so many immigrant kids do: she worked. She saved. She plotted. This is Yutsil in one small moment. Because she has options: bitterness or alchemy. She tends to choose the second one.

Her first job was at McDonald’s. She was eighteen.

Not because she didn’t have the grades for college, she did.

Not because she didn’t have the hunger for it, she did.

“I was hell-bent on getting a degree,” she said, like the degree was a shoreline and she was swimming toward it in heavy clothes.

She researched states where she could qualify for in-state tuition after living there a certain amount of time. New York happened to be one of them. (It didn’t hurt that it was 2010/2011, the golden age of indie, when you could convince yourself that culture alone could keep you warm.)

She moved to New York and enrolled at Hunter College, Upper East Side, a city that is both gorgeous and indifferent.

Academically, she was fine.

Existentially, it was brutal.

“Not the academics,” she told me. “The staying alive in New York.”

Three jobs. Two classes at a time. A life narrowed down to survival math.

And then, when she came back to North Carolina in early 2013, her life cracked open in a way that only sounds small if you’ve never lived without it:

She finally got DACA status.

We tend to name these things casually, driver’s license, paperwork, the ability to work legally, but the weight of it sits heavy beneath the words. These are things people born here rarely notice. These are the kind of things people take for granted until you tell them you couldn’t have it.

That’s when she started at Chick-fil-A.

August 2013: cashier.

Within a year: corporate office.

Then it went hard and fast and dizzying in the way it does when you’re competent and the world finally decides to reward you for it.

And there’s a line she said that I can’t stop thinking about, because it’s the line so many women, so many oldest daughters live inside:

“When you’re good at something, you think, is this what I’m supposed to do?”

She learned a lot. She also knew it wasn’t the end of her story.

And then she was fired, not for performance or failure, but for an arbitrary time-punch policy.

She didn’t fight it.

“I took the keys off my keychain,” she told me, “put them on the desk, and walked out.”

Sometimes the door that closes isn’t a tragedy.

Sometimes it’s the only thing strong enough to shove you toward your actual future.

“If I hadn’t gotten fired,” she said, “I would have probably been complacent and stayed… and I would really hate my life right now.”

Salem College came next. Political science. A history minor she wishes had been a major. School, finally, not as an interruption but as nourishment.

She worked while studying. Ran Louie & Honey as general manager. Built systems. Worked the floor. Balanced responsibility with curiosity. Thriving here didn’t look glamorous, it looked like endurance paired with agency.

Fifteen years after high school, she finished her degree.

Now she’s in law school at Wake Forest University. Waitlisted at Yale.

If you’ve ever wondered what law school feels like, Yutsil will tell you:

“Torture. Horrible. It’s a hazing ritual.”

Grades drop all at once. Exams are 100% of the grade. There are no little checkpoints, no “you’re doing fine” along the way.

“It’s all essay-based,” she said. “Who wrote the better one?”

Five essays in 4.5 hours plus 41 multiple-choice questions.

“Only masochists survive,” she said, I laughed.

And then she said something else, something quieter, something I don’t want to skim past: It’s hard to focus on studying when you’re living with the fear of what could happen to your family.

“No one outside of this will ever know what that’s like,” she told me.

That sentence has a whole universe inside it.

Her family is what she calls “the most mixed-status family.”

Yutsil has DACA.

Her two siblings and parents are all of different statuses.

Her parents came in their late 20s/30s. Her father is a pastor and a general contractor. Her mother has been a nanny for a decade, underpaid, deeply loved by the kids, and tethered by the emotional trap so many caretakers know: these are my kids.

And then there’s the reality that lives under everything:

ICE rumors in town. Anxiety in the house. The plan.

“If one of us gets the axe,” she said, “we’re all leaving. We’re not fighting it.”

A sentence so simple, it’s devastating.

Because that’s what people don’t understand about immigration, how nuanced it is, how rooted you can become, how your life can be entirely here while the law keeps insisting you’re temporary.

People ask her: “You’ve been here 20-something years. Why aren’t you a citizen yet?”

And she answers with the only honest truth:

“There is really no pathway unless you have a viable U.S. citizen relative… or you’re wealthy. Otherwise, there is literally no pathway. None.”

//

What people miss, when they talk about immigration like it’s a personal failing or a moral puzzle, is how much of it has always been luck disguised as law.

Yutsil knows this because it’s written into her family history.

My mother. Her grandmother. U.S. citizens, not because they planned it, not because they navigated the system better, but because they arrived in a particular year, during a particular war, when policy briefly cracked open just enough to let them through. Reagan-era amnesty. A roll of the dice.

Other families arrived a year too late. Or a decade too early. Or under a different administration. Same work ethic. Same fear. Same love. Entirely different outcomes.

Immigration doesn’t move in straight lines. It moves in cycles. Open, then closed. Invitation, then exclusion. The country has done this before, again and again. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of European immigrants entered through Ellis Island with comparatively minimal barriers. For most, the process took hours or days, not years. With Chinese immigrants at the turn of the twentieth century. With Mexican Americans who were deported despite citizenship. With Irish, Italian, Jewish families once deemed undesirable. With Japanese Americans imprisoned on U.S. soil. After 9/11, the walls went back up. Not because migration ended, but because tolerance did.

Geography is chance. Timing is chance. None of us choose where we’re born or when the rules will change. And yet we keep pretending the system is a test people either pass or fail.

Yutsil, and those like her, live inside that contradiction: a life entirely rooted here, shaped by U.S. schools, U.S. labor, U.S. ambition, while the law insists on calling her temporary.

That’s the quiet violence of it. Not the crossing itself, but the waiting. The constant recalculation. The knowledge that belonging can be revoked, not because you did something wrong, but because the political mood shifted.

Which is why DACA didn’t feel like paperwork. It felt like oxygen.

//

Yutsil refuses to let bitterness be the thing that defines her.

She chose law not to fix everything, but to understand the machinery. To work adjacent to power without losing herself to it. To protect people, especially creatives and small businesses, from being exploited by systems they didn’t build.

She knows her limits. She knows she is an empath. She knows certain kinds of legal work would break her. So she chooses sustainability over martyrdom. She chooses contribution that allows her to keep living.

Her parents support her, not because they expect her to carry everything, but because they know who she is. She doesn’t know how to sit still. She loves learning. She is building something with the long view in mind.

Everything she does now, she says, is for them too. For dignity. For rest.

Toward the end of our conversation, Yutsil said something that made me laugh and ache at the same time.

Her parents support her in law school at 32 years old because they know how she is: she doesn’t know how to sit down.

And also:

“They low-key know I’m their retirement plan.”

She said it with humor, but there was tenderness there too.

“They always tell me, ‘Don’t put that pressure on yourself.’ And I’m like, no. You’ve done so much. I want you to retire with dignity.”

And then, like a spark:

“I also operate out of spite,” she said, smiling through the sentence. “I love proving my haters wrong.”

Spite can be a survival tool.

So can love.

So can a mother who wanted education but couldn’t afford it, and now watches her daughter walk into rooms that once felt impossible.

There’s a moment Yutsil described, standing inside Yale Law School for the first time, that I keep replaying.

“If I could tell six-year-old me,” she said, “who had just crossed the border, had no idea what was happening…that one day she would even set foot inside a law school…it blows my mind.”

This is what this all means to me. This is a record of the long way.

The way people become who they are despite the rules meant to stop them.

Yutsil’s story is not just: immigrant girl goes to law school.

It’s:

a life built through barriers, humor, work, rage, tenderness, systems-thinking, and the stubborn belief that possibility is still worth chasing, even in chaos.

She told me she’s 1/6th done with law school. Two and a half years to go.

“This time next year,” she said, “I’ll be halfway through.”

And then, like a vow:

“I’ve got to buckle the fuck up.”

Under the same moon, we’re all buckling up in different ways.

But some of us have been doing it since we were six.

Note for the Reader:

This piece comes from a conversation with Yutsil Hernández, but it is also shaped by the many conversations we don’t often get to hear: what it means to grow up in U.S. schools while undocumented, how immigration law quietly rearranges timelines, how fear and ambition coexist in the same household.

Yutsil’s story is not offered as inspiration, it’s offered as testimony.

My hope with this series is to make room for complexity, for nuance, for the truth that thriving is not always loud or linear. Sometimes it looks like endurance. Sometimes it looks like choosing possibility anyway.